After Beethoven completed the three String Quartets commissioned by Prince Galitzin, he was on a roll. He continued to have new ideas for String Quartets and was also tempted by publishers who described a growing market for these compositions and would pay good money for them.

By the end of July 1826, Beethoven had completed a new String Quartet in C♯ minor, published posthumously as Opus 131. Surprisingly, the only other time he had written a composition in the key of C♯ minor was in 1801 and the “Moonlight” Sonata (Day 140). But if Beethoven had lived a few more years and finished the Requiem that he had been planning, that too would probably have been in C♯ minor.

The Opus 131 String Quartet is radically structured: The score has seven numbered movements (but two are very short), and although they are aurally clearly differentiated, they all run together as if seven parts of one continuous movement.

On the manuscript of the Opus 131 String Quartet delivered to his publisher, Beethoven had written “patched together from pieces filched here and there.” The Schott Sons were somewhat alarmed, so Beethoven had to ensure them it was just a joke and “it is really brand new.”

In his book on The Beethoven Quartets, Joseph Kerman writes about Opus 131 that

the uniqueness of this quartet lies exactly in the mutual dependence of its contrasted parts, or as some will prefer to put it, in their organic interrelation. Freedom, normality, and the solution of conflicts may surely be bound up with this. The Quartet in C♯ minor is the most deeply integrated of all Beethoven’s composition; in which respect it stands at the very opposite end of a spectrum from the Quartet in B♭. …

To be quite precise about it, the players are required to move in strict rhythm from No. 2 to 3, 3 to 4, and 6 to 7, and are required to move directly after a fermata note or a fermata rest from No. 1 to 2, 4 to 5, and 5 to 6. These fermata rests breathe high expectancy; they take next to no time at all. There must be no break of attention, no catching of breath, no coughs or tuning or uncrossing of legs. (p. 326)

#Beethoven250 Day 358

String Quartet No. 14 in C♯ Minor (Opus 131), 1826

The Attacca Quartet during their complete Beethoven cycle. (That’s my wife sitting in the first pew at the left; I’m to her left out of view.)

The first movement of the Opus 131 String Quartet is marked Adagio, and although Beethoven frequently had Adagio introductions to first movements, his only other Adagio first movement just happens to begin his only other C# minor composition: the “Moonlight” Sonata.

Opus 131 begins with an Adagio fugue, the instruments entering beginning with the first violin and continuing down the staves. In its serenity and beauty, it is very unlike the Grosse Fuge finale of Beethoven’s previous String Quartet (Day 355). Michael Steinberg writes:

It is as though Beethoven, after the inspired and magisterial audacities of the Grosse Fuge, were rendering a peace offering to the fugue gods.” (Winter & Martin, ed, The Beethoven Quartet Companion, p. 245.

For Angus Watson, the fugue subject consists of two contrasting phrases. The first four notes are “a metaphor for despair or spiritual exhaustion” while the following nine are “a metaphor for serenity and divine consolation” (Beethoven’s Chamber Music in Context, p. 266)

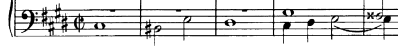

The first two full measures consist of a pair of semitone intervals. Interestingly, a similar sequence of notes occurs in the Bach Fugue in C♯ from Book 1 of the Well-Tempered Clavier:

Beethoven had been familiar with the Well-Tempered Clavier since he was a boy, and he continued to play from it in his adulthood. Carl Czerny said that his own edition of the WTC was based on the way Beethoven played it.

The second movement of the Opus 131 String Quartet is a pleasant jaunty dance in 6/8 time. It seems like it should be a Scherzo, but it refuses to cooperate in providing a contrasting Trio section, and the various episodes don’t drift away sufficiently to be a rondo.

The Opus 131 third movement is a short 11-measure transition that starts out Allegro and then becomes Adagio with some first violin runs before yielding to the next movement.

The literal and figurative centerpiece of Opus 131 is an Andante theme with at least six variations. Martin Cooper describes “the theme’s tender, almost willowy gracefulness and flexibility.” (Beethoven: The Last Decade, p. 396)

The theme is presented with cello pizzicato, becoming arco at Variation 1, where the theme is extensively ornamented and seemingly stretched out into aching passages and simultaneously compressed. (What is this sorcery?)

Variation 2 is a zippier rustic dance, trading off the melody between violin and cello, and then getting everyone involved. The sparse and austere Variation 3 is marked Andante moderato e lusinghiero, a word that can be translated as flattering, coaxing, or seductive.

Variation 4 shifts to 6/8. Angus Watson writes:

Beethoven creates a scene of pure enchantment, rich in varied tone-colours, contrapuntal detail and unexpected surprises; a limpid dream-like waltz, in which the dancers become so wrapped up in themselves, their thoughts and feelings that they scarcely notice the two-note pizzicatos at the end of each phrase. (p. 270)

But however odd the 4th variation might sound, the 5th is weirder. At times, it seems almost like one of Beethoven’s hymnlike passages, but there’s a strange pulling back and forth that prevents it from falling into a groove.

The 6th variation shifts to a 9/4 Adagio that begins with fairly steady pulses that evolve into lovely themes with interruptions by an insistent cello that wants everybody to turn it into a march.

What follows next has been described as a 7th half variation and coda, or a series of four short variations. Trills introduce a 2/4 Allegretto, but nobody’s really in the mood to keep it up for long, and the movement ends with departing pizzicato.

The 5th movement of Opus 131 is merely marked Presto, but it has the energy and wit associated with a Scherzo — “like children in a playground” Angus Watson says. The Trio section (if that’s what it is) is marked piacevole (pleasant). No change in meter or key, but it’s a folksy contrast. Beethoven knows we’re having fun so he repeats the Scherzo and Trio and threatens another. In the coda, he specifies sul ponticello for 18 measures and the players bow very near the bridge for an eerie nasal sound. Although Beethoven didn’t invent the technique, he had never used it before. It was familiar to some Baroque composers but Beethoven probably first encountered it in Haydn’s Symphony No. 97.

A startling contrast to the loud chords that end the 5th movement of Opus 131 comes with the Adagio 6th movement. At first it seems like it might be another mournful Cavatina, but it’s only 28 measures long, and it’s terminated with the unison octaves of the finale.

The Opus 131 finale is the wildest of rides. It begins with angry unison bursts, quickly launches into a sardonic dotted rhythm and then emits plaintive cries from the sickroom. Beethoven juggles and combines these rambunctious themes with an agility so effortless and carefree that we are confronted with a conundrum: How can there be so much fury, so much pain, but handled with such grace? It is the supreme triumph of art, the exhilaration of turning life’s horrors into an expression of exultation and ecstasy.

Beethoven is said to have believed the Opus 131 String Quartet to be his greatest (Thayer-Forbes, p. 982), but on another occasion, he refused to pick a winner among them:

Each in its way. Art demands of us that we shall not stand still.

At some point in your life, you might learn that Leonard Bernstein (among others) conducted string orchestra arrangements of Beethoven string quartets, and you might wonder “I know in principle that such a thing is a travesty, but how bad could it be?”

Do you really need to ask?

#Beethoven250 Day 358

String Quartet No. 14 in C♯ Minor (Opus 131), 1826

For purposes of morbid curiosity only: A string orchestra arrangement conducted by Leonard Bernstein.

In his characteristically lush prose style, Richard Wagner wrote:

In illustration of such a venerable day from Beethoven’s inmost life I will choose the great C-sharp minor Quartet … The lengthy opening Adagio, surely the saddest thing ever said in notes, I would term the awaking on the dawn of a day “that in its whole long course shall ne’er fulfil one wish, not one wish!” [Goethe’s Faust] Yet it is alike a penitential prayer, a communing with God in firm belief of the Eternal Goodness. — The inward eye then traces the consoling vision (Allegro 6/8), perceptible by it alone, in which that longing becomes a sweet but plaintive playing with itself: the image of the inmost dream takes waking form as a loveliest remembrance. And now (with the short transitional Allegro moderato) ‘tis as if the master, grown conscious of his art, were settling to work at his magic; it re-summoned force he practices (Andante 2/4) on the raising of one graceful figure, the blessed witness of inherent innocence, to find a ceaseless rapture in that figure’s never-ending never-heard-of transformation by the prismatic changes of the everlasting light he casts thereon. — Then we seem to see him, profoundly gladdened by himself, direct his radiant glances to the outer world (Presto 2/2): once more it stands before him as in the Pastoral Symphony, all shining with his inner joy; ‘tis as though he heard the native accents of the appearances that move before him in a rhythmic dance, now blithe now blunt (derb). He looks on Life, and seems to ponder (short Adagio ¾) how to set about the tune for Life itself to dance to: a brief but gloomy brooding, as if the master were plunged in his soul’s profoundest dream. One glance has shewn him the inner essence of the world again: he wakes, and strikes the strings into a dance the like wereof the world had never heard (Allegro finale). ’Tis the dance of the whole world itself: wild joy, the wail of pain, love’s transport; utmost bliss, grief, frenzy, riot, suffering; the lightning flickers, thunders growl: and above it the stupendous fiddler who bans and bends it all, who leads it haughtily from whirlwind into whirlpool, to the brink of the abyss; — he smiles at himself, for to him this sorcery was the merest play. — And night beckons him. His day is done.

About the same time that Beethoven completed the Opus 131 String Quartet, his nephew Karl, now 19 years old, had become exceptionally unhappy concerning his future career, and the domineering and suffocating guardianship of his uncle. On 6 August 1826, in what was probably a cry for help rather than a sincere attempt at suicide, Karl fired a gun at this head twice, and wounded himself badly enough to require extended medical care. On his recovery, it was decided that Karl should enter the military. He was assisted in this by a Baron Joseph von Stutterheim, who was rewarded by Beethoven with the dedication of the Opus 131 String Quartet.