The canon on the text “Es muss sein” (WoO 196) has assumed an elevated importance in Beethoven’s compositional history because the phrase also shows up at the beginning of the finale of the score of his last string quartet, Opus 135, coming up soon (Day 361).

There is some uncertainty whether Beethoven wrote the canon in April 1826, or in late July or early August. According to Karl Holz (as related in Thayer-Forbes p. 976), it was composed in connection with performances of the Opus 130 String Quartet:

There was talk of other performances of the Quartet. Schuppanzigh was indisposed to venture upon a repetition, but Böhm and [violinist Joseph] Mayseder were eager to produce the work at one of their quartet parties at Denbscher’s house.

Ignaz Dembscher was an official of some sort with the Austrian War Department. He was a wealthy music lover and often held concerts at his home.

But Dembscher had neglected to subscribe for Schuppanzigh’s concert and had said that he would have it played at his house, since it was easy for him to get manuscripts from Beethoven for that purpose. He applied to Beethoven for the Quartet, but the latter refused to let him have it, and Holz, as he related to Beethoven, told Dembscher in the presence of other persons that Beethoven would not let him have any more music because he had not attended Schuppanzigh’s concert. Dembscher stammered in confusion and begged Holz to find some means to restore him to Beethoven’s good graces. Holz said that the first step should be to send Schuppanzigh 50 florins, the price of the subscription. Dembscher laughingly asked, “Must it be?” (“Muss es sein?”) When Holz related the incident to Beethoven he too laughed and instantly wrote down the following canon:

#Beethoven250 Day 357

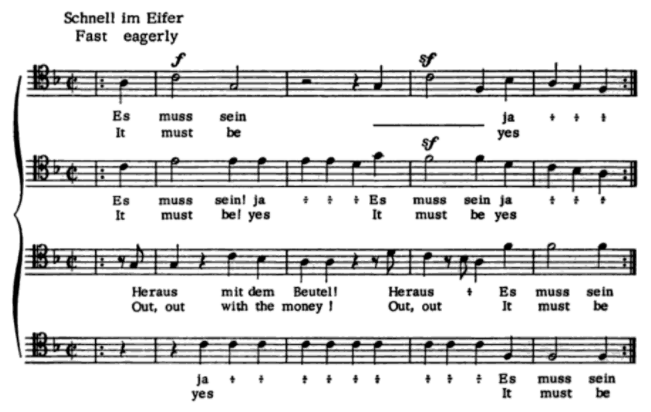

Canon “Es muss sein” (WoO 196), 1826

A studio recording of the four-part canon.

Thayer continues the discussion of the origins of the WoO 196 canon by writing that “The joke played a part in the conversations with Beethoven for some time.” (Thayer-Forbes, p. 977)

One can easily image this becoming a catchphrase with Beethoven and his circle. A situation would come up and someone would ask “Muss es sein?” and someone else would invariably say “Es muss sein!” and everybody would laugh and order another round.

But just as the simple Seyn oder Nichtseyn in Schlegel’s translation of Hamlet’s soliloquy evokes deep philosophical issues, so might also the fatalistic refrain of Muss es sein? and Es muss sein!

Es muss sein! is also a catchphrase for Tomas, the protagonist of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Tomas had been introduced to the quartets and sonatas of Beethoven through his wife Tereza, and he wonders if that phrase applies to their love:

We all reject out of hand the idea that the love of our life may be something light or weightless; we presume our love is what must be, that without it our life would no longer be the same; we feel that Beethoven himself, gloomy and awe-inspiring, is playing the ‘Es muss sein!’ to our own great love. (Part 1, Chapter 17)

But based on something Tereza once told him, Tomas doesn’t think this is true, and he “came to the conclusion that the love story of his life exemplified not ‘Es muss sein!’ (It must be so) but rather ‘Es könnte auch anders sein’ (It could just as well be otherwise).”

Towards the end of the novel (spoiler alert!), Tomas rejects the deterministic imperative of Es muss sein!:

Love is our freedom. Love lies beyond “Es muss sein.”

Though that is not entirely true. …

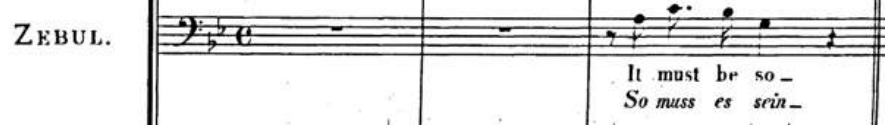

The first occurrence of the words Es muss sein in Beethoven’s WoO 196 canon are set to the notes A-C-G. In a 2003 article in The Musical Times, “New Light, but Also More Confusion, on ‘Es muss sein’”, Gerald Silverman notices that the first recitative of Handel’s oratorio Jephtha begins with the notes A-C-B♭-G as a setting of the English text “It must be so.” The B♭ is a short passing note that could be eliminated if reducing the text to three syllables:

Beethoven could have consciously or subconsciously been quoting Handel in the WoO 196 canon. But while positing this theory, Silverman’s article raises other problems with it concerning Beethoven’s access to Handel’s scores.