Nobody wishes illness on anyone and particularly not Beethoven, who throughout his life clearly suffered enough.

But if a particular Beethoven illness resulted in one of the most extraordinary compositions ever written, might we be excused for feeling a bit ambivalent?

In April 1825, Beethoven became afflicted with what was later diagnosed as an intestinal inflammation. Ludwig Rellstab in his reminiscences (Day 344) mentions not being able to visit Beethoven in April because of this illness.

On 18 April 1825, Beethoven wrote to Dr. Anton Braunhofer, who had treated him periodically since 1820:

My esteemed Friend, I am not feeling well and I hope that you will not refuse to come to my help, for I am in great pain. If you can possibly visit me today, I do most earnestly beg you to come … (Beethoven Letters, No. 1359)

Braunhofer was also a Professor of Natural History at the University of Vienna. In 1820, Beethoven dedicated his WoO 150 song “Abendlied unterm gestirnten Himmel” (Day 318) to him.

From Beethoven’s conversation books we learn of Braunhofer’s medical orders:

No wine, no coffee, no spice of any kind. I’ll arrange matters with the cook.… Then I will guarantee you full recovery which means a lot to me, understandably, as your admirer and friend. … You must do some work in the daytime so that you can sleep at night. If you want to get entirely well and live a long time, you must live according to nature. You are very liable to inflammatory attacks and were close to a severe attack of inflammation of the bowels; the predisposition is still in your body. (Thayer-Forbes, p. 945)

By 7 May 1825, Beethoven was able to move to Baden, and said in letters that he was convalescing. A week later, on 13 May 1825, Beethoven wrote an unusual letter to Dr. Braunhofer (Beethoven Letters No. 1371) with a mock dialog between doctor and patient:

Doctor: How are you, my patient?

Patient: We are rather poorly — we still feel very weak and are belching and so forth. I am inclined to think that I now require a stronger medicine, but it must not be constipating — Surely I might be allowed to take white wine diluted with water, for that poisonous beer is bound to make me feel sick — my catarrhal condition is showing the following symptoms, that is to say, I spit a good deal of blood, but probably only from my windpipe. But I have frequent nose bleedings, which I often had last winter as well. And there is no doubt my stomach has become dreadfully weak, and so has, generally speaking, my whole constitution. Judging by what I know of my own constitution, my strength will hardly be restored unaided.

Doctor: I will help you, I will alternate Brown’s method with that of Stoll.

Patient: I should like to be able to sit at my writing-desk again and feel a little stronger. Do bear this in mind — Finis

In mentioning Brown and Stoll in his letter of 13 May 1825, Beethoven is alluding to two opposing schools of medicine. An Appendix on “Beethoven’s Medical History” by Edward Larkin in Martin Cooper’s Beethoven: The Last Decade 1817–1827 (1970) clarifies:

The medical atmosphere is clearly still that of the eighteenth century. Brown died in 1788; his treatment was to cure by opposites, weakness by stimulation, stoppage of the bowels by purgation, etc. His methods had great vogue and are credited with killing more people than the Napoleonic wars. Stoll (d. 1787) represented what has been mainstream medicine since Hippocrates, i.e., to rely on and try to supplement the vis medicatrix naturae, a homely example of which is applying foments to an inflammation.

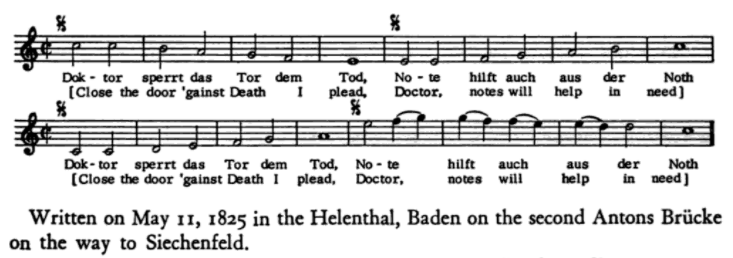

In his letter to Dr. Braunhofer on 13 May 1825, Beethoven also included a canon (WoO 189). Here’s how it’s reproduced in Thayer-Forbes, p. 946, including a translation of Beethoven’s text, and where he was when he composed it two days earlier:

The first line is usually translated more poetically as “Doctor bars the gateway to death.” The German text has a pun on the words Note (“notes” such as musical notes) and Noth (“need”).

In his biography of Beethoven, Lewis Lockwood writes:

The canon text, which Beethoven wrote himself, gives every hint that during this illness, his sense of mission, his urgent desire to complete these quartets … were now (with much difficulty and with Braunhofer’s help) holding the door closed against death. (p. 44)

In the opening essay of Beethoven Essays, Maynard Solomon translates the text of the canon in a way that perhaps indicates more accurately what Beethoven was really trying to convey. He writes:

Even a frivolous canon, composed as a gift to his physician in 1825, tells the story of his fears, his helplessness, and his faith in music as countervailing force against death. ‘Doctor, bar the door to Death! Music too will help in my hour of need.’ For Beethoven, music, whatever else it represented, was also a form of protective magic, in whose efficacy he placed his full trust. (p. 28)

#Beethoven250 Day 345

Canon “Doktor sperrt das Tor” (WoO 189), 1825

A studio performance presented with what appears to be the autograph score.

On 17 May 1825, Beethoven had recovered enough to write his nephew Karl from Baden:

I am beginning to compose a fair amount again. But in this extremely gloomy, cold weather it is almost impossible to do anything — (Beethoven Letters, No. 1372)

By the end of May 1825, Beethoven wrote to Dr. Braunhofer

We thank you for the advice which was well given and well followed by means of the wheels of your inventive genius; and we inform you that in consequence we now feel very well. (Beethoven Letters No. 1383)

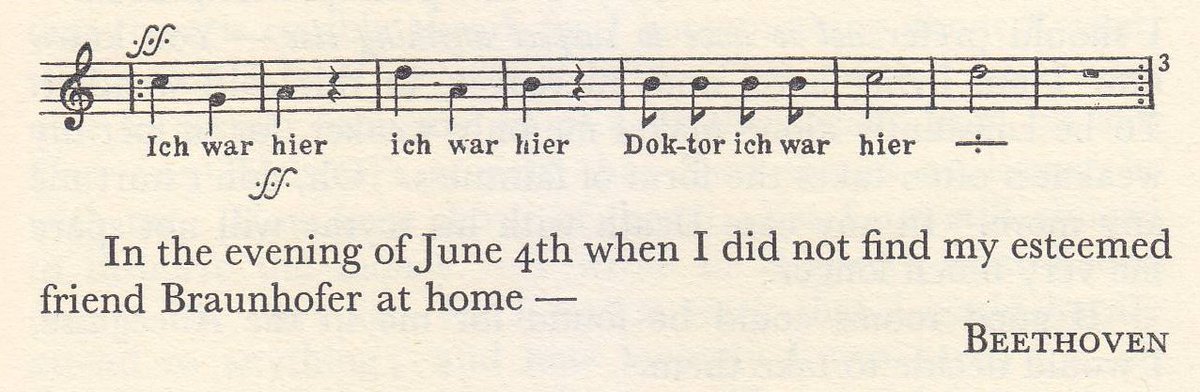

In early June, Beethoven made a little excursion from Baden into Vienna (about a three-hour trip by coach) and called on Dr. Braunhofer. He was not at home, so of course Beethoven left a little canon (WoO 190). This is from Emily Anderson’s “Letters of Beethoven,” No. 1385:

#Beethoven250 Day 345

Canon “Ich war hier, Doktor” (WoO 190), 1825

A studio performance with animated score and (probably unnecessary) English translation.

During that month of May 1825 as Beethoven was recovering from his illness and getting back to his desk, he conceived and composed the exceptionally moving and heartfelt slow central movement of what was to become the Opus 132 String Quartet.