Beethoven wrote four tiny canons in 1823. One is the WoO 185 “Edel sei der Mensch” canon (Day 332). The others are catalogued as WoO 183, WoO 184, and WoO 202, and will be discussed today.

Our knowledge of the origins of the canon “Bester Herr Graf” (WoO 183) relies on a note by Anton Schindler, so some doubt exists as to its authenticity. On 20 February 1823, at the tavern The Golden Pear, Beethoven had a disagreement with Count Moritz Lichnowsky concerning a contract with the publisher Steiner. Beethoven dashed off a setting of “Bester Herr Graf, Sie sind ein Schaf!” or “Dear Count, you are a sheep!” an animal that in many languages refers to a gullible fool. The score is printed in Thayer-Forbes, p. 838:

#Beethoven250 Day 335

Canon “Bester Herr Graf” (WoO 183), 1823

A studio recording with multiple voices singing in unison.

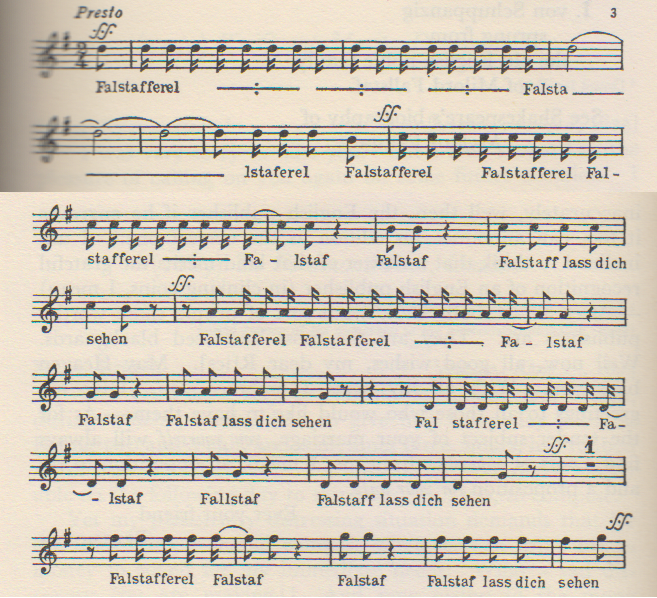

In 1823, Beethoven’s old friend, the violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh, returned to Vienna after a seven-year absence in London and Russia. In earlier years, Schuppanzigh was a frequent target of Beethoven’s fat shaming (Day 142), and Beethoven wasn’t about to reform. On 26 April 1823, Beethoven wrote Schuppanigh a letter consisting of not much more than music for a canon based on the text “Falstafferel, lass dich sehen!” or “Little Fallstaff, let us see you.” The canon is signed “amici amicus Beethoven.”

Notice the symbols above the staff indicating where the multiple voices are to enter.

On the reverse, Beethoven wrote:

To the highly born

I. von Schuppanzig

sprung from

the old English noble family

of Milord Fallstaff.

See Shakespeare’s biography of

Mylord Fallstaff.

The Beethoven-Haus site has this first edition of the “Falstafferel, lass’ dich sehen” canon (WoO 184) as published by Die Musik in 1903. The single vocal line has here been expanded into a five-voice canon:

The complete “Falstafferel, lass’ dich sehen” canon was also published beginning on page 255 of this 1908 German edition of Beethoven letters.

#Beethoven250 Day 335

Canon “Falstafferel, lass’ dich sehen” (WoO 184), 1823

The stuttering repeated syllables give this canon a peculiarly modern sound.

The final canon of 1823 (catalogued as WoO 202) was written for Marie Pachler-Koschak, whose piano playing Beethoven admired. In 1817 he wrote to her:

I have not yet found anyone who performs my compositions as well as you do; and I am not excluding the great pianists, who often have merely mechanical ability or affectation. (Beethoven Letters No. 815)

Frau Pachler was in Vienna again in 1823, and on her departure on 27 September, Beethoven wrote a short piece of music in the family autograph album. The text is contraction of the last line end of Friedrich von Matthisson’s poem “Opferlied”:

Das Schöne zum Guten

The Beautiful to the Good.

The actual last line of the poem is “Das Schöne zu dem Guten!” Beethoven had set “Opferlied” to music in 1798 as a song WoO 126 (Day 112) and had also been experimenting with setting it using multiple voices.

Following page 48, this German book on Beethoven from the early 20th century reproduces the autograph of the WoO 202 music as it appeared in Marie Pachler-Koschak’s album:

The WoO 202 autograph is deciphered and reproduced as No. 242 on page 152 in Thayer’s 1865 chronological catalog of Beethoven works.

This is a puzzle canon, so more steps are required to determine where to introduce the voices.

#Beethoven250 Day 335

Canon “Das Schöne zum Guten” (WoO 202), 1823

A studio recording of the solved puzzle canon.

In some rooms in Baden that Beethoven had rented from a blacksmith,

Beethoven was in the habit of scrawling all kinds of memoranda on his shutters in lead pencil — accounts, music themes, etc. A family from North Germany had noticed this in the previous year and had bought one of the shutters as a curiosity. The thrifty smith had an eye for business and disposed of the remaining shutters to other summer visitors. When Beethoven was informed by an apothecary at Baden of this strange transaction, he burst into homeric laughter. (Thayer-Forbes, p. 868)