Although Beethoven was baptized as a Roman Catholic, his actual religious beliefs were much more personal and often obscure. In the essay “The Quest for Faith” (reprinted in the book Beethoven Essays), Maynard Solomon tries to trace the metamorphosis of these beliefs.

Beethoven came of age in the Enlightenment, and “his search for faith remained centered on the standard Enlightenment precepts of humanity, universal brotherhood, progress, morality, and reason.” Beethoven likely believed in God as evidenced by manifestations of nature. It is well known that Beethoven was fond of a book by Christian Sturm, Betrachtungen uber die Werke Gottes in der Natur (“Observations Concerning God’s Works in Nature”). (Here’s an English abridgement published in 1798).

Yet, the religious revival that accompanied the end of the Napoleonic Wars probably also influenced Beethoven, as well as his personal challenges involving the legal struggle over his nephew Karl and, of course, his worsening hearing. He became more interested in Eastern religions as well as more orthodox Christianity.

In his later life, Beethoven’s more ardent religious beliefs are apparent in the song “Abendlied unterm gestirnten Himmel” (Day 318) and his Solemn Mass of 1822 — the Missa Solemnis.

Beethoven first made a promise in June 1819 that he would compose a Mass for the solemnization of the Archduke Rudolph’s promotion to Archbishop of Olmütz a year hence. But as the Missa Solemnis grew in complexity and length, Beethoven missed the deadline. By a lot.

As Beethoven was composing the Missa Solemnis, he researched the Mass tradition in German music, early music such as Palestrina, more recent music (Bach, Handel), and he made certain he understood the meaning of every Latin word in the liturgy to set it to music properly. Warren Kirkendale’s article “New Roads to Old Ideas in Beethoven’s ‘Missa Solemnis’” from The Musical Quarterly, Oct. 1970, is a fascinating study of how Beethoven balanced the traditional and innovative in this work.

Over 600 pages of sketches exist for the Missa Solemnis, but that quantity is apparently not unusual for some of Beethoven’s other late works. The most number of pages of sketches is for the Opus 131 String Quartet in C♯ Minor, coming up in 1826.

The Missa Solemnis probably reached something close to its final form in the summer of 1822, but Beethoven continued to fiddle with it. He gave the Archduke Rudolph a presentation copy on 19 March 1823, but it wasn't published until 1827.

The Missa Solemnis is sometimes called the Mass in D Major to distinguish it from the Opus 86 Mass in C Major that Beethoven composed in 1807 (Day 205). The earlier Mass is a little over half the length of the Missa Solemnis.

Perhaps it’s a reflection of the amount of work that Beethoven devoted to the Missa Solemnis, but he said that he considered it to be his best work, at least up to that time. In a letter to the Grand Duke Ludwig I of Hess, Darmstadt on 5 February 1823, Beethoven wrote:

The undersigned has just finished his latest work which he considers to be the most excellent product of his mind. It is a grand solemn Mass for four solo voices, with choruses and a full grand orchestra; and it can be performed as a grand oratorio. (Letters No. 1134)

My chief aim when I was composing this grand Mass was to awaken and permanently instil religious feelings not only into the singers but also into the listeners. — Beethoven on the Missa Solemnis, 16 September 1824 (Beethoven Letters No. 1307)

The Missa Solemnis is about 80 minutes long and consists of five movements corresponding to the texts of the Mass Ordinary:

- Kyrie

- Gloria

- Credo

- Sanctus (with Benedictus)

- Agnus Dei

Four solo voices are included in addition to the chorus, but they do not sing arias.

#Beethoven250 Day 327

Missa Solemnis (Opus 123), 1822

The Amsterdam-based Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century uses period instruments with a modestly sized orchestra and chorus.

The texts in the Missa Solemnis are in Latin except for the opening Kyrie section in Greek: “Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison” meaning “Lord, have mercy. Christ, have mercy.” The score instructs that it be played “Mit Andacht,” meaning “With Devotion” or “Devoutly.”

The Kyrie is the shortest section in the Missa Solemnis and the most subdued, but with lovely interchanges between the chorus and soloists. Notice the key, tempo, and meter changes from “Kyrie eleison” to “Christe eleison” to emphasize the distinction between God and Christ.

The Gloria section of the Missa Solemnis has a longish text beginning with “Gloria in excelsis Deo, et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis,” meaning “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men of good will.”

Beethoven begins the Gloria of the Missa Solemnis with a vibrant Allegro Vivace that includes trumpets and timpani in which we can hear brief premonitions of the 9th Symphony and the first of many fugal sections in the work.

Martin Cooper sees in the Gloria of the Missa Solemnis the excesses

that foreshadow the kolossal that was to mark the music of Wagner and much else of late nineteenth-century German art and reach its extreme limit in Richard Strauss’s Alpinsinfonie and Symphonia Domestica, in Mahler’s Eighth Symphony and Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder. But what, in Wagner’s Tristan, only thirty-five years after the Missa Solemnis, was a conscious intention to stun the listener, to bludgeon him into submission, was in Beethoven’s case something very different — a vision of power and magnificence to be celebrated with every resource of his art. (Beethoven: The Last Decade, 1970 edition, p. 238)

Alto, tenor, and bass trombones appear for the first time in the Gloria. These evoke the custom of playing multiple trombones from towers, a tradition that Beethoven contributed to a decade earlier when he composed three Equali for four trombones (Day 256).

A Larghetto section in the Gloria handles the text “Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis” (“You who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us”), but the music again becomes triumphant with “Quoniam tu solus sanctus” (“For thou alone art holy”) and ends with fugues.

The Credo section of the Mass has the longest text: the Nicene Creed established in 325 A.D. to combat various heresies of the era. It begins “Credo in unum Deum, patrem omnipotentem” — “I believe in one God, the father almighty.” The dogmas of the Nicene Creed have various levels of importance and controversy, and hence pose a challenge to the composer: which items to musically linger over and which items to rush past, and how to do that.

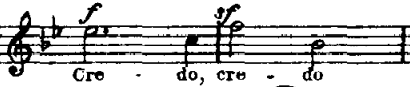

Beethoven manages the Credo of the Missa Solemnis with several changes of tempo and meter. The crucial word “Credo” (“I believe”) is set in a distinctive melodic and rhythmic pattern that reappears throughout the movement.

The Credo shifts to Adagio with words “Et incarnatus est de spiritu sancto ex Maria virgine” (“And was incarnate by the holy ghost of the Virgin Mary”). If the passage here sounds strangely medieval, there’s a reason for that: Beethoven had learned through his studies of ancient music that the medieval Dorian mode was associated with chastity, so while this passage appears to be in D minor (with a B♭ in the key signature), the B’s in the score are marked with a natural sign.

Beginning with “Crucifixus etiam pro nobis sub Pontio Pilato” (“He was crucified under Pontius Pilate”), Beethoven composes a mini-Passion. The music becomes particularly anguished, but with “et ascendit in coelum” (“and ascended into heaven”) the music does likewise.

The Credo ends with an enormous double fugue on the words “et vitam venduri saeculi” (“and the life of the world to come”) and “Amen.” What might have been a tedious litany of dogma becomes a triumphant affirmation of eternal life.

#Beethoven250 Day 327

Missa Solemnis (Opus 123), 1822

A big orchestra and chorus performance with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony and the Vienna Singverein conducted by Andrés Orozco-Estrada.

The fourth movement of the Missa Solemnis is the Sanctus, which also includes the Benedictus, so it’s sometimes referred to by both names or by just Sanctus. It’s one continuous movement with the two parts joined by an orchestral interlude that Beethoven labels “Preludium.”

The Sanctus text comes from Isaiah 6:3: “Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus, Dominus Deus Sabaoth. Pleni sunt coeli et terra gloria tua! Osanna in excelsis” or “Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of Hosts. Heaven and earth are fully of thy glory! Hosanna in the highest.”

The Sanctus movement in the Missa Solemnis begins Adagio, again with the injunction to play “Mit Andacht” (devoutly) and with canonic passages in the orchestra and chorus. At “Pleni sunt coeli,” an energetic and joyful Allegro choral fugue erupts.

Following the Sanctus in the Mass Ordinary, Consecration takes place: the bread and wine become the body and blood of Jesus, perhaps accompanied by a solemn improvisation on the organ. Beethoven instead includes a dark-hued hymn-like orchestral interlude labeled “Preludium.”

In a Mass, a candle would be lit following the Consecration, symbolizing the divine presence of Jesus. At the very end of Beethoven’s Preludium, a solo violin in a high register becomes the aural equivalent, accompanied at first just by flutes. The Benedictus section then begins.

The Benedictus text is from Matthew 21:9 when Jesus comes into Bethlehem and the crowds shout “Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini. Osanna in excelsis” or “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest.”

With only brief pauses, the violin solo continues through the entire Andante Benedictus. Despite the simple (and perhaps glaring) symbolism of the solo violin as the divine presence of Jesus, the Benedictus weaves an enticing spell that is often unbearably beautiful.

In his essay “Music at Night,” Aldous Huxley complements a June night on the Mediterranean in the 1920s by randomly choosing a record to play:

suddenly the introduction to the Benedictus in Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis begins to trace its patterns on the moonless sky.

The Benedictus. Blessed and blessing, this music is in some sort the equivalent of the night, of the deep and living darkness, into which, now in a single jet, now in a fine interweaving of melodies, now in pulsing and almost solid clots of harmonious sound. it pours itself, stanchlessly pours itself, like time, like the rising and falling, falling trajectories of a life. It is the equivalent of the night in another mode of being, as an essence is the equivalent of the flowers, from which it is distilled.

There is, at least there sometimes seems to be, a certain blessedness lying at the heart of things, a mysterious blessedness, of whose existence occasional accidents or providences (for me, this night is one of them) make us obscurely, or it may be intensely, but always fleetingly, alas, always only for a few brief moments aware. In the Benedictus Beethoven gives expression to this awareness of blessedness. His music is the equivalent of this Mediterranean night, or rather of the blessedness at the heart of the night, of the blessedness as it would be if it could be sifted clear of irrelevance and accident, refined and separated out into its quintessential purity.

The Missa Solemnis concludes with the Agnus Dei. Text is partially from John 1:29: “Agnus Dei qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis” or “Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us,” and then with the last phrase “dona nobis pacem” — “grant us peace.”

The Agnus Dei begins with a solemn Adagio, and the soloists and chorus keep coming around back to that word “miserere” in their desperate pleas for mercy.

With the first appearance of the phrase “Dona nobis pacem” in the Agnus Dei, the tempo quickens to Allegretto and the meter changes to a pastoral 6/8. Beethoven marks in the score “Bitte um innern und äussern Frieden” — “Pray for inner and outer peace.”

In the pastoral section of the Agnus Dei, now it’s the word “pacem” that the singers drag out and sometimes even chant. And for good reason, for soon we hear war drums and military trumpets. The invasion is brief but ominous, vanquished by a choral fugue on “Dona nobis pacem.”

The military drums that interrupt the Agnus Dei come twice more, first with more intensity and then seemingly in retreat, as if the persistent evocation of “Dona nobis pacem” has warned them away.

Beethoven’s inclusion of battle music in the Agnus Dei has been compared to the last movement of Haydn’s Missa in Tempore Belli (Mass in Time of War), but the two works are quite different in effect and perhaps more importantly, intention:

Haydn composed his Mass in Time of War in 1796 during a period of war with France following the Revolution. Haydn’s Mass is militaristic, and his invocation of battle is triumphant, very much in accordance with the pro-war decrees of the Austrian government at the time.

By 1822, the war was long over, but Beethoven likely still remembered the horrifying invasion of Vienna (Day 216). The sudden appearance of military music in Beethoven’s Agnus Dei is unexpected and terrifying, much like the thunderstorm in the 6th Symphony.

Haydn’s Mass is seeing soldiers off to war with the orders for them to “grant us peace.” In Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, the Mass has been interrupted by invaders, and it’s necessary to call upon the music of “Dona nobis pacem” to force them to retreat.

Beyond issues of war and peace, Maynard Solomon detects in the Agnus Dei other conflicts as well, and not just for Beethoven:

Beethoven’s ongoing conflict between faith and doubt is revealed in the Missa Solemnis. As [musicologist Walter] Riezler knew, in the Dona nobis pacem, with its sounds of strife and warfare and its anguished cries for peace, both inner and outer, Beethoven “dared to allow the confusion of the world outside to invade the sacred domain of church music.” In this sense, the Missa Solemnis forecasts the theological questions and doubts — along with the warfare between science and religion — that were to dominate the intellectual background of the nineteenth century. (Beethoven, pp. 403–4)

For Jan Swafford, the Missa Solemnis ends “in an atmosphere of fragmentation and irresolution.”

In Beethoven’s Agnus Dei, there is no integration and no resolution of the violence and disruption. The rumbling of drums at the end pictures war receding, at the same time reminds us of our terror. At one point Beethoven sketched a triumphant ending, labeled the receding drum idea peace. Then he decided that, no, to finish this gigantic work of faith he wanted a curt, ambiguous, unresolved ending….

At the end there is no triumph of faith, no triumph of peace, no triumph at all. God has not answered humanity’s prayers, its demands, its terrified pleas for peace. The drums have receded, but they are still out there, and they can come back. (Beethoven, pp. 824, 5)

The Choral Society of Grace Church — a church that I can see from the window of my New York City apartment — performed the Missa Solemnis last year, and recently created a series of videos that explore the music with the live performance.

#Beethoven250 Day 327

Missa Solemnis (Opus 123), 1822

John Maclay, Music Director of the Choral Society of Grace Church, discusses the five movements separately and then presents a live performance.

In its length, complexity, and overwhelming power, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis was considered inappropriate for liturgical use. But it could not legally be performed in a Viennese concert hall except in excepts and translated into German. For these reasons, the Missa Solemnis was first performed in its entirety in St. Petersburg on 7 April 1824, and then the Kyrie, Credo, and Agnus Dei with German translations in Vienna on 7 May 1824— the same concert that featured the premiere of the Symphony No. 9.