After many struggles and personal anguish, a long legal battle concluded on 8 April 1820 when the Court of Appeals ruled in Beethoven’s favor that he could have joint guardianship (with Karl Peters) of his nephew Karl.

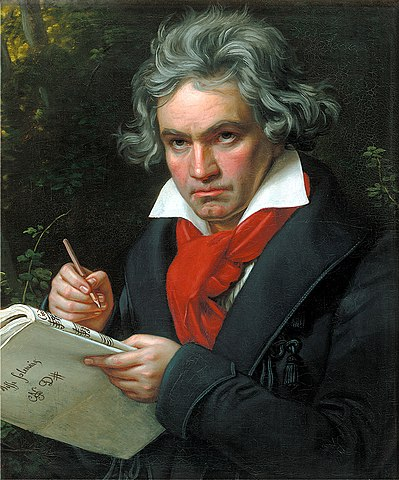

Between 1819 and 1820, the artist Joseph Karl Stieler painted a portrait of Beethoven that in its romantic idealization has become the most famous image of the composer.

This is Beethoven as comic-book superhero.

To John Clubbe, Stieler portrayed Beethoven as a revolutionary:

Stieler used an unusually large bright red scarf to set off both the blue coat and the white collar. Except for military uniforms, red was rare for male attire. The choice must have been Beethoven’s. During one of the century’s most repressive years, the composer again wished to clothe himself in blue, white, and red. Not only is red the color of revolution, but the artist uses red as an accent in the painting on Beethoven’s chin and fingers, even more on his cheeks and lips. The rosy cheeks imply a much younger and healthier man than Beethoven now was. But, though pale and sick in reality, he is portrayed in radiant health and in the full vigor of maturity.

In short, Stieler depicted Beethoven not only in his attire but in his whole being as the embodiment of revolution. Here was someone with a lot of fight left in him. (Beethoven: The Relentless Revolutionary, p. 375)

Having Beethoven as a renter might have been challenging at time:

In the summer of 1820 Beethoven went to Mödling again, but he did not take lodgings in the Hafner house for the very sufficient reason that the proprietor had served notice on him in 1819, that he could no have it longer on account of the noisy disturbances which had taken place there. (Thayer-Forbes, p 761)

Beethoven’s song “Gedenke mein!” (“Remember me!,” WoO 130) is dated “Mödling, 11 September 1820” in an autograph of the score at Beethoven-Haus.

This autograph is not in Beethoven’s hand but is believed to have been copied from the original.

The inscription reads:

Prior to the departure of his Imp. Highness, the most serene Archduke Rudolph, an exercise for his Imp. Highness, our well-beloved Archduke Rudolph, from L. v. Beethoven.”

It might be that Beethoven intended Rudolph to consider this short song as the basis for another set of piano variations, similar to “O Hoffnung” (Day 308), or perhaps for another type of composition exercise.

The author of the text of “Gedenke mein!” is unknown. In English, the text is:

Remember me!

I shall be thinking of you!

Ah, only hope makes bearable

The pain of separation.

— Paul Reid, “Beethoven Song Companion,” pp. 152–3

#Beethoven250 Day 319

“Gedenke mein!” (WoO 130), 1820

An animated score accompanies this studio recording by Peter Schreier

Although Beethoven’s “Gedenke mein!” was composed in 1820, it has a catalog number of WoO 130 among songs composed around 1805. That mistake resulted from confusing this song with “Andenken,” WoO 136 (Day 186), which begins with the line “Ich denke dein” (“I think of you”).