“Live only in your art, for you are so limited by your senses. This is nevertheless the only existence for you.” — Beethoven’s daybook, c. 1816

In the compositionally sparse year of 1816, Beethoven’s only major works were “An die ferne Geliebte” (Day 294) and the Piano Sonata No. 28 in A major, which he began in 1815, finished in November 1816, and published as Opus 101.

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 28 is a twin of his Cello Sonata No. 4, Opus 102, No. 1 (Day 287). Both have a somewhat indeterminate number of movements with an opening Andante, a faster second movement, an Adagio interlude, and a first movement recall before the finale.

#Beethoven250 Day 299

Piano Sonata No. 28 in A Major (Opus 101), 1816

A sensitive performance earlier this year by Korean pianist Minsoo Sohn.

The Piano Sonata No. 28 opens with a relaxed and conversational fantasy-like Andante in 6/8 time. The overall feel is of yearning pensiveness. Off-beat chords dislodge us from certainty, and then take us into darker corners, though only briefly.

For the 2nd movement of the Piano Sonata No. 28, Beethoven forgoes the traditional Minuet (as he had often done) and his customary replacement Scherzo. Instead, he presents a March in 4/4 time, still structurally like a Minuet movement with a Trio section and a da capo repeat.

The 2nd movement March of the Piano Sonata No. 28 is so jaunty and angular that it seems closer in personality to a Scherzo despite the quadruple meter. The Trio section is a surprising canon, & surprising how lyrical it is:

He writes the direction dolce three times, perhaps because this trio is one of his most extraordinary demonstrations of how to make something gracefully delicate out of contrapuntal combinations and motifs that almost anyone else would have considered intolerably awkward. (Charles Rosen, Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas, p. 215)

What follows the Not-Really-a-March movement of the Piano Sonata No. 28 is a Not-Quite-a-Movement short Adagio introduction that nevertheless puts us in a whole different mode before flowing into a short reminiscence of the opening movement.

The energetically joyful finale of the Piano Sonata No. 28 is a contrapuntal orgy. Beethoven first teases us with organically emerging fugal passages that don’t quite develop, a canon likewise, before launching into a full-fledged fugue, ending likewise with another tease.

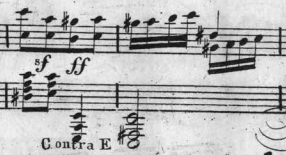

In the final movement of the Piano Sonata No. 28, Beethoven uses a low note on the piano that his contemporaries might not have encountered before, so he thoughtfully labels it “Contra E”:

Beethoven dedicated his Piano Sonata No. 28 to Dorothea Ertmann (born Dorothea Graumann in 1781), who was one of the preeminent interpreters of Beethoven’s piano music during his lifetime. He called her Dorothea Cecilia (referring to the patron saint of music) and wrote:

Please accept now what was often intended for you and what may be to you a proof of my devotion both to your artistic aspirations and to your person — That I could not hear you play at Cz[erny]’s recently was due to an indisposition which at last seems to be yielding to my healthy constitution — I hope to hear from you soon how the Muses are faring at St. Pölten, and whether you cherish any regard for your friend and admirer, L. v. Beethoven — Beethoven Letters No. 764

As the Piano Sonata No. 28 was being engraved, Beethoven wrote “Quite by chance I have hit on the following dedication.” He had already used both traditional Italian tempo markings and German descriptions for the movements and now he had a similar idea for the title:

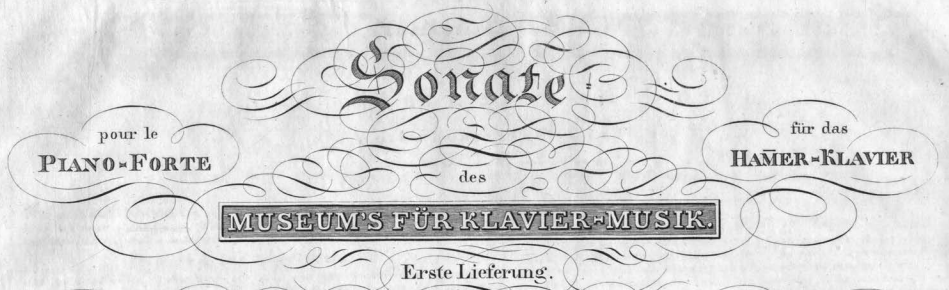

Sonata for the Pianoforte or — — Hämmer-Klavier.

Beethoven wrote: “Hämmer-Klavier is certainly German and in any case it was also a German invention.” (Beethoven Letters No. 742) It is not true that the piano was a German invention.

There was some later confusion about the spelling:

In regard to the title, a linguist should be consulted as to whether Hammer or Hämmer-Klavier or, possibly, Hämmer-flügel should be inserted. (Beethoven Letters No. 746)

The title page of the first edition had another spelling altogether. However, this is not the Beethoven piano sonata that came to be known by the nickname “Hammerklavier.” That would be Beethoven’s next piano sonata: the 29th in B♭ major.

Beethoven’s publisher S.A. Steiner issued Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 28 as the first installment of a “Museum für Klaviermusik” dedicated for preserving “only music products of recognized value, compositions that are particularly distinguished by aesthetically pure design developed with art, charm and clarity.”

Both Beethoven and Steiner knew that this was a work destined for posterity.

In another letter to Sigmund Anton Steiner (who he addressed with the abbreviation “Lt Gl” for Lieutenant General), Beethoven again wrote about titles for his Piano Sonata No. 28 (Letters No. 749):

As for the title of the new sonata, all you need do is to transfer to it the title which the Wiener Musikzeitung gave to the symphony in A [the 7th], i.e. ‘the sonata in A which is difficult to perform’. No doubt my excellent Lt Gl will be taken aback, for he will think that ‘difficult’ is a relative term, e.g. what seems difficult to one person will seem easy to another, and that therefore the term has no precise meaning whatever. But the Lt Gl must know that this term has a very precise meaning, for what is difficult is also beautiful, good, great and so forth. Hence everyone will realize that this is the most lavish praise that can be bestowed, since what is difficult makes one sweat

For Lewis Lockwood, the Opus 101 Piano Sonata is one of several works during this less fruitful era in Beethoven’s career that seem to signal a “change in his evolution toward the transcendental” (Beethoven, p. 347):

what has been seen as a “fallow” period might be reconceived as a period of self-reconstruction, a necessary questioning of previous approaches and the gestation of new ones, in which a new compositing personality within him was in the process of emerging.