In a letter dated 13 February 1814, Beethoven wrote a brief aside:

My opera is also going to be staged, but I am revising it a great deal. (Beethoven Letters No. 462)

The opera was Fidelio, not heard since 1805 and 1806 and now being revised once again.

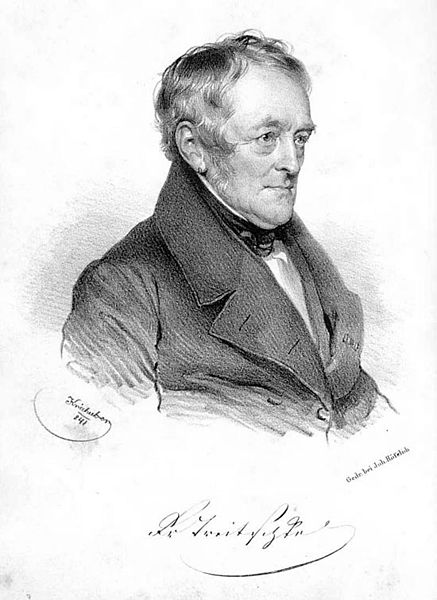

In revising Fidelio, Beethoven was working with Georg Friedrich Treitschke, who had come to Vienna in 1800 at the age of 24. He started as an actor, then worked his way up to stage manager and then to the management of the Theater-an-die-Wien and the Kärthnerthor-Theater.

Georg Friedrich Treitschke was putting together a project of his own: a one-act patriotic singspiel entitled “Die gute Nachricht” (“The Good News”) in which a father promises her daughter’s hand in marriage to the first man who can bring him news that Paris has fallen.

Treitschke’s “Die gute Nachricht” assembled music from several different composers. The Overture and three musical numbers were composed by Johann Nepomuk Hummel, and a Mozart aria was repurposed. Beethoven was responsible for the final rousing chorus, “Germania.”

It was not known when “Die gute Nachricht” would be premiered because the plot depended on the allied armies reaching Paris. That occurred on 31 March 1814. The news reached Vienna by 10 April, and the work was premiered at an already scheduled concert on 11 April.

Beethoven’s “Germania” is for bass, chorus, and orchestra. Treitschke’s text (translation on Wikipedia is unabashedly patriotic, praising the anti-Napoleon alliance of Czar Alexander (Russia), Friedrich Wilhelm (Prussia), and Austrian emperor Franz.

#Beethoven250 Day 265

Germania Chorus from “Die gute Nachricht” (WoO 94), 1814

This is a studio recording. The work is not often performed live.

For the concert which premiered “Die gute Nachricht,” Beethoven was also persuaded to play the piano part in the Archduke Trio (Day 247).

At one of the rehearsals, composer and violinist Louis Spohr heard Beethoven practice:

It was not a treat, for, in the first place, the piano was badly out of tune, which Beethoven minded little, since he did not hear it; and secondly, on account of his deafness there was scarcely anything left of the virtuosity of the artist which had formerly been so greatly admired. In forte passage the poor deaf man pounded on the keys till the strings jangled, and in piano he played so softly that whole groups of tones were omitted, so that the music was unintelligible unless one could look into the pianoforte part. I was deeply saddened at so hard a fate. If it is a great misfortune for any one to be deaf, how shall a musician endure it without giving way to despair? Beethoven’s continual melancholy was no longer a riddle to me. (Thayer-Forbes, pp. 577–8)

By the time of the premiere of “Die gute Nachricht,” Napoleon had already abdicated. The final Act of Abdication is dated 11 April 1814 and identifies Napoleon as “the sole obstacle to the restoration of peace in Europe.” On 3 May, he was delivered to exile on the island of Elba.